The town that I grew up in was officially named the Gold Coast by real estate developers.

Through urban planning, tourism boards, real estate and advertising, the town was structured to deliver a fantasy to the people who visited, as well as its residents.

I thought that the drug trade, the rape, the violence, the sleazy underworld business was just a normal part of life. I thought that everyone lived this way.

In part it was because I had learned, through visual culture, that seedy places didn’t look like this. Dangerous places looked dark, filled with broken windows and alleyways.

There was no reason to be wary when the sun shone down every day on white folk dressed in polo shirts, aqua swimming pools, luxury SUVs and endless white sand beaches.

By the time I was 13, I could get my hands on any kind of contraband I knew how to pronounce. I knew of at least two friends who had been gang raped by the time I was 17.

By the time I was 18, I’d seen two people get their throats cut and bleed to death in the living room of a friend’s house.

All of these events took place in homes that were designed and sold as a utopia of waterfront living.

They don’t tell you that the waterways that thread these neighbourhoods are literally populated by bull sharks.

It wasn’t until I was 27 years old that I moved to another city with my family.

And it wasn’t until I was 30 that I felt compelled to go back to the Gold Coast to answer the questions that drove me to become a nomad, drawn to places like Florida and Atlantic City over and over again like some Lynchian Groundhog Day, photographing what I saw but never really being satisfied.

It was going back to ground zero that illuminated many things about who I am as a photographer and the issues that drive me.

Going back and self-publishing my first book, my debut statement, about this town and my experience there has given me the answers that I need to move forward.

It has become a way for me to communicate to the outside world a fragility in the social fabric that we buy into.

Rich people can steal, white men can kill and people can cook meth in a home with a pool and a nice front lawn.

This story originally appeared in Huck 46 – The Documentary Photography Special II. Get it from the Huck Shop or subscribe to make sure you don’t miss another issue.

Check out the portfolio of photographer Ying Ang or buy her Gold Coast book.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

This erotic zine dismantles LGBTQ+ respectability politics

Zine Scene — Created by Megan Wallace and Jack Rowe, PULP is a new print publication that embraces the diverse and messy, yet pleasurable multitudes that sex and desire can take.

Written by: Isaac Muk

As Tbilisi’s famed nightclubs reawaken, a murky future awaits

Spaces Between the Beats — Since Georgia’s ruling party suspended plans for EU accession, protests have continued in the capital, with nightclubs shutting in solidarity. Victor Swezey reported on their New Year’s Eve reopening, finding a mix of anxiety, catharsis and defiance.

Written by: Victor Swezey

Los Angeles is burning: Rick Castro on fleeing his home once again

Braver New World — In 2020, the photographer fled the Bobcat Fire in San Bernardino to his East Hollywood home, sparking the inspiration for an unsettling photo series. Now, while preparing for its exhibition, he has had to leave once again, returning to the mountains.

Written by: Miss Rosen

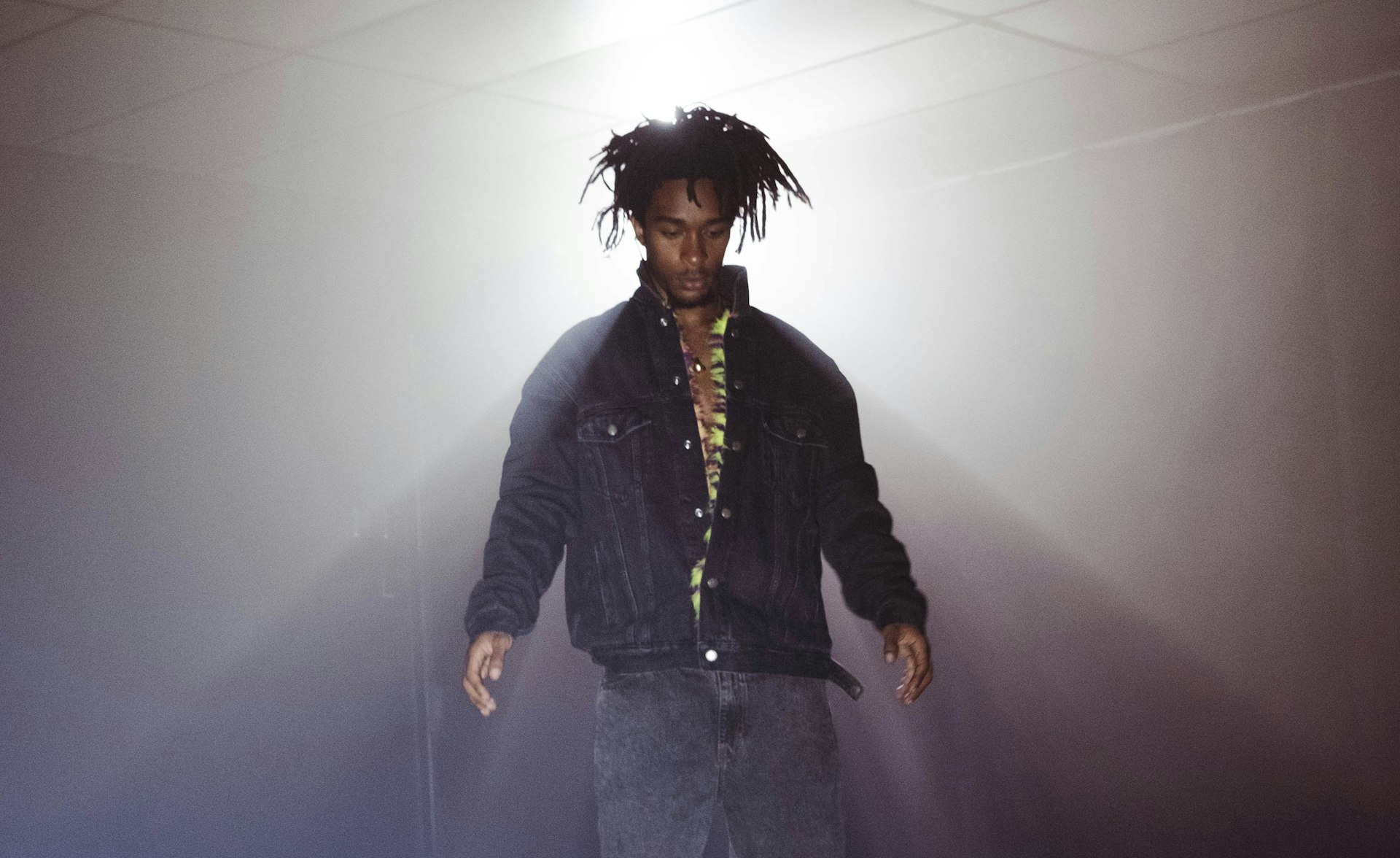

Ghais Guevara: “Rap is a pinnacle of our culture”

What Made Me — In our new series, we ask artists and rebels about the forces and experiences that have shaped who they are. First up, Philadelphian rap experimentalist Ghais Guevara.

Written by: Ghais Guevara

Gaza Biennale comes to London in ICA protest

Art and action — The global project, which presents the work of over 60 Palestinian artists, will be on view outside the art institution in protest of an exhibition funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai

Ragnar Axelsson’s thawing vision of Arctic life

At the Edge of the World — For over four decades, the Icelandic photographer has been journeying to the tip of the earth and documenting its communities. A new exhibition dives into his archive.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai