Meet the Paratriathlete who cheated death

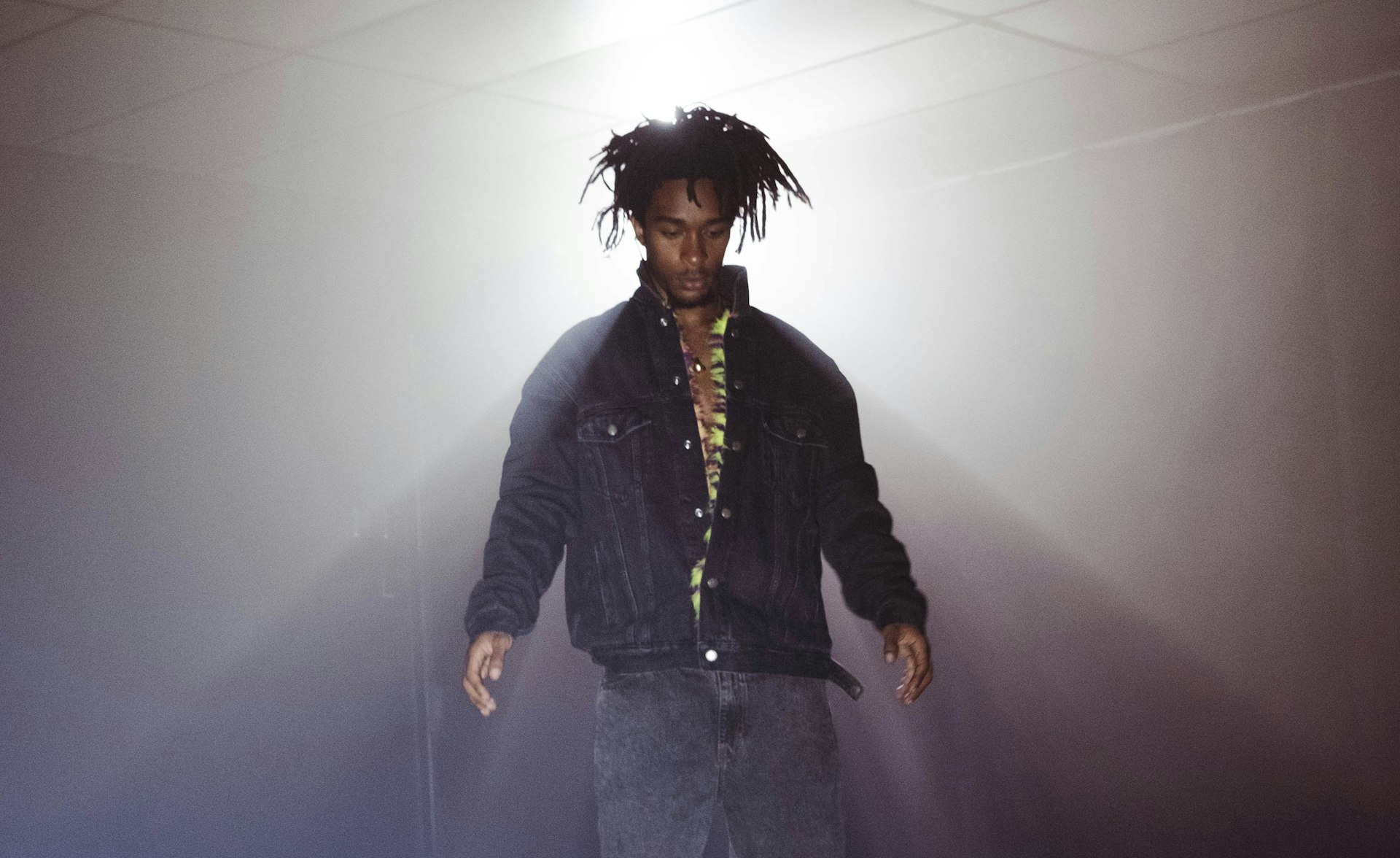

- Text by Sheridan Wilbur

- Photography by Theo McInnes

- Illustrations by Moira Letby

George Peasgood had conflicting feelings last October. It had been one year since the cycling accident where everything stopped. The next day was his 28th birthday. “Safe to say it was better than last year,” jokes George. “But it was emotional.”

He cried more than 10 times by lunch then cried some more on his birthday. For many athletes, the afterlife is not death but retirement. And those dates packed a one-two punch, reminding him how close he came to the end.

It’s starting to feel like spring in Loughborough, 100 miles north of London and home to British elite athletics. Trees are blossoming, days are longer, and George is lively after his first solo ride in a year-and-a-half. He greets me inside his townhouse. There’s relaxing ambient music playing but the mood already feels sillier than calm. I spot a whiteboard beside the TV with daily goals (Monday: ‘look good,’ Tuesday: ‘be sexy’, Friday: ‘get money’), two Paralympic medals lie atop stacks of magazines on his desk and could easily be mistaken as coasters, dog chew toys litter the floor.

As a toddler, George “lost a fight with a lawnmower” leading to 15 reconstructive surgeries on his left leg. He has “zero negative feelings about that anniversary because it was so physical.” Embracing physical pain is a sensibility he’s had since a kid. His parents, both Ironman triathletes, influenced him into a lifestyle of gruelling endurance sports. At 15, he joined WaldenJNR, a local junior triathlon club in Essex, training for two hours on Saturday mornings. “It gave my dad a chance to go grocery shopping,” he says. More importantly, his dad gave him the chance to transform into an elite athlete.

“If it’s not on Strava, did it even happen?”

In triathlon, George excels in the water and on the bike, then holds on for the run, usually the hardest due to his leg impairment. In 2013, George won his first major medal at the ITU World Championships. In 2016, he made it to Rio, finishing seventh. George has won the British Paratriathlon National Championships four times and at 17 was the youngest para-triathlon medallist ever, but his biggest accomplishment was his latest: two medals from Tokyo, silver in the PTS5 triathlon and bronze in the C4 cycling road time trial. He had Paris 2024 in his sights but things can change in a spin of a wheel.

On 1 October 2022, the day before his 27th birthday, George went for a ride with his then-girlfriend. 200 yards away from home he called out, “One more sprint.” He gave a final push, then his foot slipped out the pedal and hurled him over the handlebars. Into immediate blackness. He sarcastically mentions now his GPS watch never uploaded the session. “If it’s not on Strava, did it even happen?”

A valid question. He has no recollection of the crash. What he’s been told: he suffered seizures at the roadside, bled from his ears, got blue-lighted to the hospital where he was diagnosed with a grade 3 diffuse axonal brain injury and was entered into the deepest level of coma. Nine in ten people with the same brain injury don’t regain consciousness. “If you google DAI Grade 3, it’s some bad stuff,” he says. His injury report also included a fractured skull, contusions to the left frontal lobe, fluid on the brain and fractures in his cheekbone, shoulder blade and collarbone.

George pulls out a grey and black helmet from his bedroom, covered in road rash-looking scratches. The MIPS (Multi-Directional Impact Protection System) technology helped protect his brain in the fall, he says. The helmet is cracked in two places. Dried blood stains remain. He returns the war relic to his closet, beside his Team Great Britain racing kits for World Championships and Paralympics.

Do you think your mindset helped you survive? “I think my mental willpower is a bit crap,” he says modestly. “In sporting terms it’s quite good, but in non-sporting terms, it’s crap.” In the preparation for Tokyo, his coach would randomly tell him to run, then stop, sprint or pick up the pace. “I got used to adjusting to what I can’t control,” he explains. Maybe his rigorous training translated beyond sport.

George spent 49 days in a coma, a number that still annoys him: “I’ve always been so particular. I love round numbers.” Fixations might lead to competitive advantages too. “Come on, why not 50?” Isn’t it more important to wake up? “I know. But I would rather wait another day. Just to say 50 days.” 49 is still a longer stint than Lent. “True,” he laughs. “I gave up being awake.”

In his coma, he only remembers wanting corn flakes and a cup of coffee in the morning, then being confused why he couldn’t eat breakfast. “The brain does this weird pretending thing,” he says. “I have other memories but I’m not sure if I remember it or just saw a photo.” The human brain wants to protect itself against trauma. Studies from Victoria University of Wellington have shown photographs can actually produce false memories.

He does vividly recall two days before the crash, at a Jimmy Carr show, the British-Irish comedian calling him up on stage. Under the spotlight, George was asked his fastest running times. “I was like Mum, what the fuck have you done?” (His mother had sent Jimmy a “bloody message” before the show, asking him to wish her son a happy birthday). But when Jimmy responded saying, ‘So you're not really para,’ George enjoyed the banter. Being para has to be acknowledged, even in jest, because it’s so entwined with his life.

Sitting in his living room, we watch his cockapoo Ivy chewing on a sneaker. “Leave it Ivy,” he says. They’re gym shoes. “Smellier the better.” George brought home this 7kg bundle of fur to lift his spirits and aid his rehab last July. “I’ve noticed the difference in how I feel, even with her being a knob.” Ivy takes this as a cue to rest on his lap. “Sometimes she’s sweet. Other times she’s a little shit.” She’s calm as a purring cat now.

Two months after the crash on 13 January 2023, George woke up to a life he didn’t believe was real. This is common for those with a traumatic brain injury or following a coma. “I hoped a minute wouldn’t be a minute,” he explains. George would reality test by counting the seconds on a clock, but he’d forget the result. “I would constantly ask if I’m a chronic vegetable.” Vegetables can't ask questions like that. “That was part of the response my family gave me,” he says.

“I’m sure I was the only person that had their turbo and bike in their private room in hospital,”

Typically, frontal lobe damage in the brain changes one’s personality. But his psychologist, friends and family say he’s the same. His emotions are just heightened. “If I’m sad, I’m proper sad and crying. If I’m happy, I’m ecstatic,” he says. “That’s probably a thing with being so close to death. I want to embrace everything.” His support team encouraged him, but he admits their optimism could be frustrating. “They’d be amazed and say, ‘Wow, George you look like you’re doing so good. How are you feeling?’ They’d expect me to say something nice back. I was like, ‘No, I’m doing crap to be honest.’”

George is candid about his mental health on Instagram, breaking conventional expectations of how elite athletes present themselves. “Everyone always thinks athletes have a good life because they get to travel and compete in other places. We have dark days too.” On a platform designed for highlights, he writes, “I’m grieving the feeling I’ve lost the life I had before.” But his vulnerability, his surges of emotion, are strengths. It means he didn’t die.

He’s written about using medication to improve his mood and thought patterns, and as George builds up tolerance to cope with lows, he enjoys highs more. He writes: “Don’t ever flatline.” Humour has snapped him out of a dream state too. Jimmy Carr remains in contact with George and his mother. “I said to him, ‘Should I start calling you dad? Now you have my mum’s number.’”

Four months after his crash, George longed for more than a laugh. “I’m sure I was the only person that had their turbo and bike in their private room in hospital,” he recounts wryly. Self-aware but self-deprecating, he describes this arrangement as ‘anal.’ Sounds more like determination. “You’ll say ‘George, your house is so messy. How are you anal?’” But inside his kitchen cabinets, he reveals over 50 water bottles neatly organised from Rio, Tokyo and national and world championships. “I like things my own way. Don’t panic, I’m not worrying where they are right now.” There’s no posture here. This is the George his family and friends know and love.

In hospital, a nurse told him he could forgo blood thinner medication by walking one daily 100m lap around the ward. “I’m an athlete. I set myself a challenge to walk 50 laps before I left.” Six months and two days after the crash, on the day he left the hospital, he completed the 5K. “I was annoyed because it took me six hours and three minutes. Couldn’t get under six.” George is never satisfied, a quality that makes him a threat to race.

Last June, his recovery sped up during a month-long stay at the Get Busy Living Centre in Leicestershire, a rehab facility for those with a life-changing injury. The goal: get too busy to stay there. George’s days were packed with physio, sports therapy and counselling sessions. Living in a private lodge, he learned to make dinner, get changed, shower, do everything for himself again.

Many would avoid intense exercise forever after it caused a life-threatening accident. “The only thing I’ve ever known is sport,” he says. But triathlon with a lower-body impairment and a traumatic brain injury presents unique challenges. His feet are significantly different sizes; one is a UK size 13 and the other is a size eight (resulting in a collection of 46 single shoes in his attic). So he has to retrain his brain to remind his legs how to run, making his lower leg impairment harder. “It’s rusty, but any form of running is liberating.” By summer 2023, George ran outside for the first time since the crash with two guides, swam in hydrotherapy and cycled on a tandem bike.

In his garage, George points out the GIANT bike he crashed on which looks rather unscathed. “Luckily my face and head took the brunt,” he says half-jokingly. He rode on that bike this morning, mentioning he passed the scene of the accident. “I almost waved and said, ‘Bye, George.’ Because that's where George 2.0 died. But I'm now George 3.0. This is my third time trying to have a good life.”

In George 3.0, his secret to life is gaining more understanding of himself and neuroscience. George’s girlfriend Emily Morris has been a “massive help.” They met online, “the same way everyone does these days.” As a netball player, she gets his athlete mentality and what he needs with brain rehab. They work on brain games sent by his occupational therapist to improve his memory “which comes and goes, so annoying.” But recently he put a list of 56 random words in order in under ten minutes without making any mistakes.

It’s early days of training but there’s freedom in starting over. George can build himself back up, learn and grow to be at the next level. “I’ve learned to be stubborn, to never take no for an answer.” Two years ago, his focus was all about the road to Tokyo. Now “it’s so much more than sports, it’s life.”

Increasingly, George is less compelled to think of triathlon as a direct path to fulfilment. But people love a comeback story. They ask him when he’s racing again. “Honestly I don’t care about Paralympics,” he says. George is quick to disavow his ambition, but he’s just as quick to train: he has another run scheduled after our interview. The 2028 Games is a long way away but elite athletes know excellence is born of action, instinct and consistency. “Obviously I care about it,” he says. “But it’s not my motivation. My only goal is to get my life back and be happy again.”

Latest on Huck

This erotic zine dismantles LGBTQ+ respectability politics

Zine Scene — Created by Megan Wallace and Jack Rowe, PULP is a new print publication that embraces the diverse and messy, yet pleasurable multitudes that sex and desire can take.

Written by: Isaac Muk

As Tbilisi’s famed nightclubs reawaken, a murky future awaits

Spaces Between the Beats — Since Georgia’s ruling party suspended plans for EU accession, protests have continued in the capital, with nightclubs shutting in solidarity. Victor Swezey reported on their New Year’s Eve reopening, finding a mix of anxiety, catharsis and defiance.

Written by: Victor Swezey

Los Angeles is burning: Rick Castro on fleeing his home once again

Braver New World — In 2020, the photographer fled the Bobcat Fire in San Bernardino to his East Hollywood home, sparking the inspiration for an unsettling photo series. Now, while preparing for its exhibition, he has had to leave once again, returning to the mountains.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Ghais Guevara: “Rap is a pinnacle of our culture”

What Made Me — In our new series, we ask artists and rebels about the forces and experiences that have shaped who they are. First up, Philadelphian rap experimentalist Ghais Guevara.

Written by: Ghais Guevara

Gaza Biennale comes to London in ICA protest

Art and action — The global project, which presents the work of over 60 Palestinian artists, will be on view outside the art institution in protest of an exhibition funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai

Ragnar Axelsson’s thawing vision of Arctic life

At the Edge of the World — For over four decades, the Icelandic photographer has been journeying to the tip of the earth and documenting its communities. A new exhibition dives into his archive.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai