David Bowie’s forgotten art book publishing company

Like most things in Bowie’s career, the art book publishing company he helped start, named 21 Publishing, was way, way over-the-top. From the beginning, there was a serious amount of money and art-world hookups.

The publishing house was started in London in 1998 by David Bowie, West End gallerist Bernard Jacobson, art-patron Sir Timothy Sainsbury and Karen Wright, editor of Modern Painters. At one time, Jacobson was named “possibly the leading art dealer of modern British art”, Sir Timothy Sainsbury is a retired Tory MP and the former chairman of Sainsbury’s supermarkets – basically an aristocrat. Karen Wright was a leading art critic who had worked with Bowie when he was on the editorial board of Modern Painters.

Despite his old-guard partners, Bowie used 21 to publish work that mocked the art-world establishment and made art accessible to the masses. “Everything was either art at an academic level or so dense with art-talk that it excluded 90 percent of the reading market,” Bowie said in a 1998 interview with ARTnews about the kickoff of the new publishing house. “We thought it might be a good thing to go at least halfway to changing that. I say halfway because some of us are maybe more populist than others.”

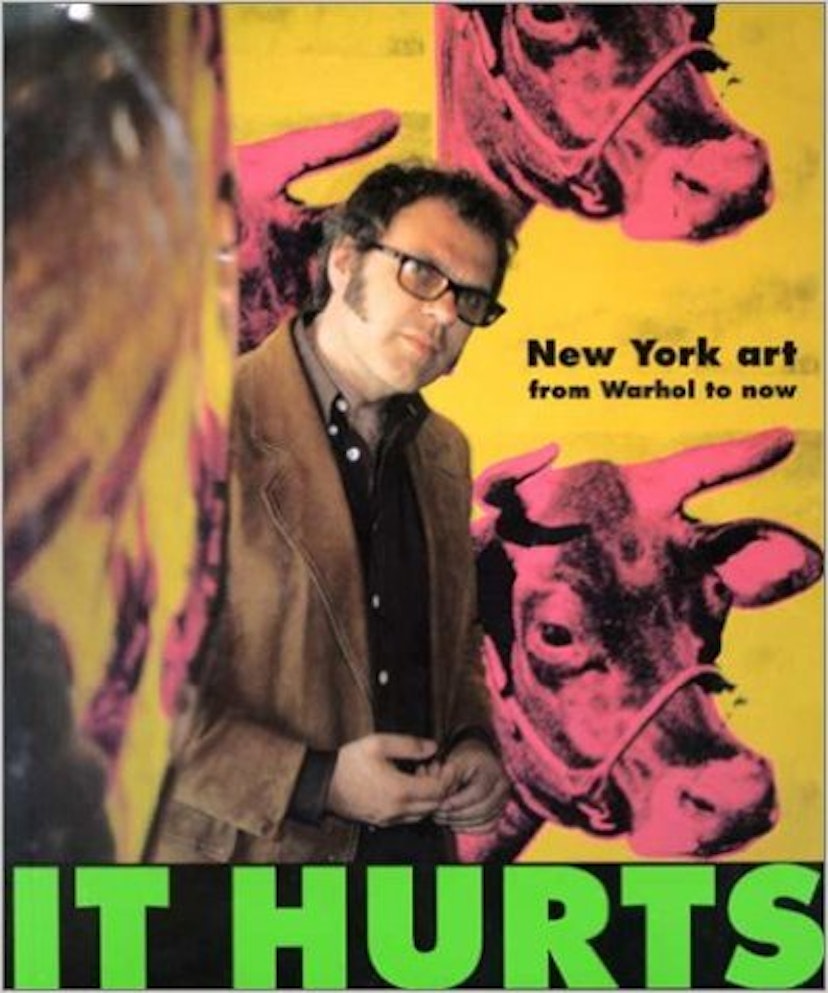

“It Hurts: New York Art from Warhol to Now” by Matthew Collings with photographs by Ian MacMillan

One of 21’s most ridiculous books was solicited by Bowie – fitting for Bowie, the book was the biography of a made-up artist. William Boyd’s Nat Tate: an American Artist 1928-1960 included fake artwork by the esteemed fake artist Nat Tate. The book was meant to get art aficionados worked up over some forgotten artist of the mid-20th century. Bowie wrote a jacket blurb for the book, and organised a release party on April Fool’s Day in Jeff Koon’s New York studio where he read, “Absolutely deadpan, to the assembled New York glitterati.” It’s reported that at the party, white-haired art folk began miraculously ‘remembering’ a retrospective of Nat Tate’s work they had seen some years ago, as if Bowie and Boyd had actually brought the artist to life. It was revealed as a hoax soon afterward.

21 published a hodgepodge of titles. Reporting the World: John Pilger’s Great Eyewitness Photographers was a photo-book that tried to make sense of the role of photojournalism and documentary photography at the dawn of the digital age. “The great documentary form, the still photograph, has become a fashion and fame vehicle, answering to the incessant demands of the market,” John Pilger wrote in the book. “As for people’s true lives, these are deemed unprofitable and therefore of minimal interest.”

“Reporting The World” by John Pilger

Matthew Collings writings had a similar goal of including normal people in art. He had three humorous, down-to-earth books of art history and commentary published by 21. The project was to rid art history of snobbery and pull it down from its ivory tower – giving art what Bowie called, “A confusing, loony relevance.” Collings remembers Bowie telling him that the rock star “didn’t collect any conceptual art, instead if he was interested in something he had his assistants make up a version for him.” Blimey!, Collings’ first book, was published while he was filming a very 90’s documentary on modern art:

Bowie had gone to art-school, but only had his solo first exhibition when he was in his 50s. “If I had some creative obstacle in the music that I was working on, I would often revert to drawing it out or painting it out,” he said in an interview with the New York Times. He had reinvented himself as an art writer when working with Modern Painters, a fairly big art magazine which catered to a wide audience. Moving on to his own indie publishing endeavours, he got more space to take up projects he was passionate about.

“The great freedom within a small indie company like ourselves is that we get the last word on how something is presented and and which books we publish. I would only be a tenacious contributor of ideas at a big house,” he said in 1998. “As long as we break even at year’s end, I think we’ll be happy.” Bowie’s work as an art book publisher is a testament to the constantly changing character of his work and the way he was able to make avant-garde art accessible for normal audiences while challenging the conception of popular music.

Latest on Huck

This erotic zine dismantles LGBTQ+ respectability politics

Zine Scene — Created by Megan Wallace and Jack Rowe, PULP is a new print publication that embraces the diverse and messy, yet pleasurable multitudes that sex and desire can take.

Written by: Isaac Muk

As Tbilisi’s famed nightclubs reawaken, a murky future awaits

Spaces Between the Beats — Since Georgia’s ruling party suspended plans for EU accession, protests have continued in the capital, with nightclubs shutting in solidarity. Victor Swezey reported on their New Year’s Eve reopening, finding a mix of anxiety, catharsis and defiance.

Written by: Victor Swezey

Los Angeles is burning: Rick Castro on fleeing his home once again

Braver New World — In 2020, the photographer fled the Bobcat Fire in San Bernardino to his East Hollywood home, sparking the inspiration for an unsettling photo series. Now, while preparing for its exhibition, he has had to leave once again, returning to the mountains.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Ghais Guevara: “Rap is a pinnacle of our culture”

What Made Me — In our new series, we ask artists and rebels about the forces and experiences that have shaped who they are. First up, Philadelphian rap experimentalist Ghais Guevara.

Written by: Ghais Guevara

Gaza Biennale comes to London in ICA protest

Art and action — The global project, which presents the work of over 60 Palestinian artists, will be on view outside the art institution in protest of an exhibition funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai

Ragnar Axelsson’s thawing vision of Arctic life

At the Edge of the World — For over four decades, the Icelandic photographer has been journeying to the tip of the earth and documenting its communities. A new exhibition dives into his archive.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai