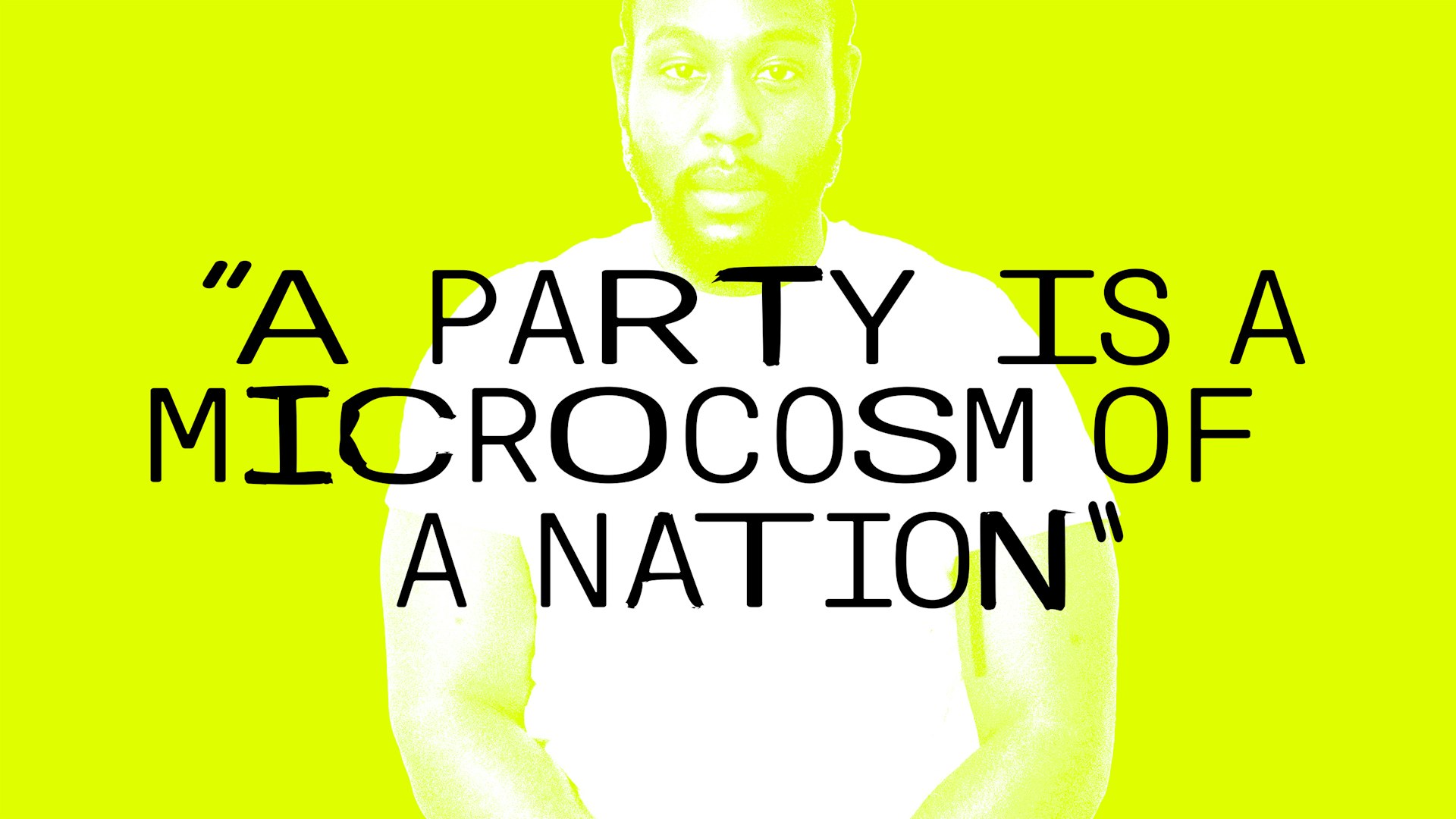

“A party is a microcosm of a nation”: Caleb Femi on the decline of the house party

- Text by Isaac Muk

- Illustrations by Liam Johnstone

This Q+A was first featured in Huck’s culture newsletter. Sign up to the mailing list here to make sure it always lands in your inbox before anyone else sees it each month.

Midnight. The shoobs is popping. The DJ is dropping straight heaters, no fillers. You’re feeling yourself. The golden ratio of drinks has been consumed. Then you look across the room, spot an ex-partner dancing with another person, and for the next hour you fight to regain that high – that once seemingly invincible mindset – but ultimately fail.

It’s a relatable experience, and one that happens to Lala – the fictional host of The Wickedest – a secret house party in London, and the title of a new book of poems from writer, filmmaker, photographer and artist Caleb Femi. “Tentacles of a fire / drowning in the dark / – what beast is this man?” she asks, presumably in her mind.

With verses, photographs, iMessage screenshots and more, The Wickedest is an immersive journey into an evening’s festivities hedonistic highs and noise complaint lows, told through interactions and intrusive thoughts. Across its pages, different poems are penned from the perspectives of its attendees, moving minute-by-minute in chronological order until the night wraps up at 4:45am.

It's a celebration of house parties – weekend warrior community spaces that for decades have formed a key part of the UK’s social and cultural fabric. But as property prices soar, noise complaints rise and social spaces increasingly move online, house parties are seemingly on the wane. We caught up with Femi to find out more about the book, the future of the shoobs, and discuss why having it large on a Saturday night should be cherished.

“Loneliness is such a rising factor in society – coming to a party, even if you don’t know anyone there, you feel like you’re part of a community and you belong. I think as a functional entity, house parties are there to strengthen the bonds between us as people, regardless of our motivations”

What struck me about The Wickedest, is that even though it’s based around a specific night in a specific place, catering for a particular set of people, there’s something universal in the experience you portray – the looks people give, or the intrusive thoughts – how did you have the idea?

It came around 2021, when I was working with Virgil Abloh on Louis Vuitton stuff. Around that time we were thinking about the final runway show, and we were talking about that idea of a party. The world had been in lockdown, and our perception of social gatherings had changed a bit. At the time, a lot of people were nervous about being in confined spaces, and nightlife in general was changing quite a lot. But we were thinking about the history and function of house parties – both in marginalised and mainstream communities.

I remember how weird those first parties were, when people wanted to be around each other but didn’t really know how to act – in some ways I don’t think it’s ever fully recovered.

No, it hasn’t, it’s forever changed. There’s some people who have taken the idea of partying to new heights, and then others who have shied away from it. There’s also been a particular rise in the policing of nightlife and because of that, a lot of people have been phased out. And for a new generation, maybe this is their first phase of being allowed out – 18, 19, 20 year olds experiencing the world for the first time. Their entry point is very different from previous generations – they can’t get accommodation at high street clubs, or put on house parties without the police turning up. If they do go out, they can’t afford it because uber prices or travel prices are ridiculous, then things like drinks and amenities – it’s expensive.

How does greater policing in nightlife manifest?

On high streets, late opening licences are no longer being given or renewed – if you’re lucky you’ll get a 1am liquor licence. You can’t legally be in high street nightclubs in the same way as you used to. There’s also forms, red tape and risk assessments, though that is the continuation of a long-standing [issue], which has been going on since the Criminal Justice Act. Then domestically in people’s houses, noise and gatherings are interwoven into people’s tenancy contracts – they say “no parties”. If you do have a party, if someone doesn’t call the police, they’re going to turn up anyway. You know what else is an interesting one? Rent prices. Now that everyone has to live together, it’s not easy to have a party – you might have one bedroom in a flat share and it might get complicated because one of the housemates is a nurse or a doctor and it gets complicated. And no one is paying two grand a month for the house to get messed up.

Why are parties important? And what made you explore the ups and downs of a party?

I think a party is a microcosm of a nation. Everybody’s narratives collide with everyone else’s at a party. You’re at the same party, but your entry points are different – some people have come to that party because they’ve had a really long week and they just want to find a way to renew their spirit, others are there because there’s someone that they love, and for some people times are hard and they’re lonely. Loneliness is such a rising factor in society – coming to a party, even if you don’t know anyone there, you feel like you’re part of a community and you belong. I think as a functional entity, house parties are there to strengthen the bonds between us as people, regardless of our motivations.

Then of course the ebb and flow is necessary, because life isn’t devoid of ebb and flows. You go to a house party and you see your ex-girlfriend – there’s an emotional sensitivity there. But it’s a by-product of being part of a community, of being in a relationship. They’re all necessary experiences in a very confined space, and that’s what I love about house parties.

Do you feel like nights out and parties are underrepresented in arts and culture?

Yeah, I think the idea of partying is oversimplified. It’s often associated with debauchery or everything that comes with being young and dumb. I think that if we take a new, refreshing lens that centres humanity, we could learn so much about ourselves. If only the arts embraced it more and allowed it to be this complex thing, rather than being one-dimensional.

I feel like there’s a big disparity in the ways working class parties or Black and Asian communities’ parties are policed and portrayed. In your book you have a section of Form 696, which has obviously been used to police UK rap and Black London music, but never a middle-class tech house night – where does that disparity come in for you?

I think it’s just part of the fabric of the society that we live in. Being part of any marginalised community, you’ll recognise that passage of play, and know that it isn’t just confined to partying, but every aspect of life that you’re fighting through. In the book I wanted to touch on it, but not too much, because then the narrative gets hijacked. With the book, I think everyone from a marginalised community would recognise that The Wickedest is from a secret house party – the location is undisclosed, the only people who have access are from that community – because if they know about it, they’re going to fuck it up. They’re going to take it apart and turn it into their own thing.

It's contrasted with a poem about Boris partying during lockdown.

Yeah, when it happened, I wasn’t surprised. But what did surprise me was 17 – I don’t think I would have gone to 17 parties in a normal year, let alone a few months in a lockdown year. But I don’t think anyone who sits on the margins would be surprised. I think some of the demonisation of house parties should be shifted to political parties, that’s where the debauchery happens and needs to be scrutinised & demonised.

So with partying on the decline for young people – socialising is moving online and spaces are disappearing – what do you think that means for society, and the next generation, who might not have gathered together and shared as much space?

Well I’m trying to stay positive. I think everything is cyclical, hopefully there is a return to house parties. As a nostalgic vehicle, but maybe the online space becomes something that they’re exasperated or bored with now that it’s the main way people communicate. Maybe it becomes a radical thing to have a house party in the future. House parties and gatherings predate anything modern we have – we have an innate attraction to wanting to congregate and celebrate one another. Even if it quietens for a few years, it won’t be able to be kept marginalised forever.

The Wickedest is published by HarperCollins

Buy your copy of Huck 81 here.

Enjoyed this article? Follow Huck on Instagram.

Support stories like this by becoming a member of Club Huck.

Latest on Huck

ATMs & lion dens: What happens to Christmas trees after the holiday season?

O Tannenbaum — Nikita Teryoshin’s new photobook explores the surreal places that the festive centrepieces find themselves in around Berlin, while winking to the absurdity of capitalism.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Resale tickets in UK to face price cap in touting crackdown

The move, announced today by the British government, will apply across sport, music and the wider live events industry.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Nearly a century ago, denim launched a US fashion revolution

The fabric that built America — From its roots as rugged workwear, the material became a society-wide phenomenon in the 20th century, even democratising womenswear. A new photobook revisits its impact.

Written by: Miss Rosen

A forlorn portrait of a Maine fishing village forced to modernise

Sealskin — Jeff Dworsky’s debut monograph ties his own life on Deer Isle and elegiac family story with ancient Celtic folklore.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Subversive shots of Catholic schoolgirls in ‘80s New York

Catholic Girl — When revisiting her alma mater, Andrea Modica noticed schoolgirls finding forms of self-expression beyond the dress code. Her new photobook documents their intricate styles.

Written by: Isaac Muk

We need to talk about super gonorrhoea

Test & vaccinate — With infection rates of ‘the clap’ seemingly on the up, as well as a concerning handful of antibiotic resistant cases, Nick Levine examines what can be done to stem the STI’s rise.

Written by: Nick Levine